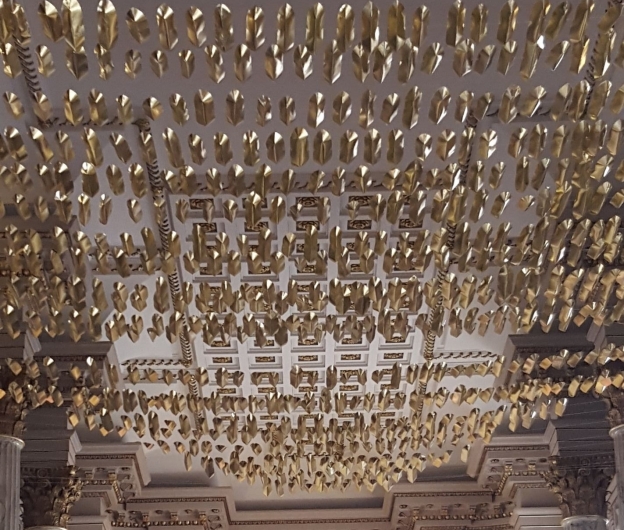

Advent feels like a pretty good time to revive a long-neglected blog. So here at the beginning of a new church year I’m posting my sermon from the Advent Carol Service at St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square, London, preached during a beautiful liturgy on the theme ‘Experiments in Hope’.

The service was broadcast on the internet by @ChurchLive using #Periscope and can still be viewed here via https://www.periscope.tv/w/1djGXbnbWABxZ

St Martin-in-the-Fields Advent Carol Service – 29th November 2015

Experiments in Hope

And the one who was seated on the throne said, ‘See, I am making all things new’.

The season of Advent, even just the word Advent, makes my spine tingle. It also makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up – and that’s not quite the same thing. The spine-tingling is caused by a magical sense of promise and expectations soon to be fulfilled. Not just the anticipation of a beautifully lit tree and enticing packages, but the excitement of the story: of angels and shepherds and wise men, and a newborn baby, God arriving among us, thrilling through our souls. In the words of Malcolm Guite ‘O founding, unfound Wisdom, finding me, O sounding Song whose depth is sounding me’: God, in Jesus, coming to be an intimate part of all that I experience, showing me how sacred and holy it is to be human.

But along with the spine-tingling why does Advent make the hairs on the back of my neck stand up? Well that’s because before we get to the lambs, the gold and the Christ-child, our Advent readings over the next few weeks will mirror some of the truly terrifying realities of the life of the world today: wars and rumours of wars, people being plucked from their daily lives at not even a moment’s notice, and judgment: the consequences when we choose not to honour life as sacred and holy.

Advent is shot through with wonder and glory and the hope of peace, but also with uncertainty, chaos and terror. That’s why it feels so real.

The theme of our worship this evening is ‘Experiments in Hope’. Our whole lives are an experiment in hope: aren’t they? A new project at work, a relationship that’s just beginning, an idea that might yet change the shape of our future – in all of these things we are experimenting. We might do it carefully, holding our breath, or more impetuously in a rush of adolescent hormones or midlife panic – but the golden thread through all of our experimenting is hope. The hope of a good outcome, a better future, a deeper connection with life, with others, and perhaps with God.

What are we experimenting with, here, tonight, in this place of darkness and light which can germinate and encourage our hopes into being? What potentially profoundly life-changing experiment in hope is going on right now?

Quite simply and profoundly we are experimenting with the hope that God is – that God is, rather than God is not. And that God cares. Cares deeply and insatiably and unstoppably and non-negotiably about us, about the world, about the dead and the grieving in Paris, about the homeless freezing on the streets of central London, about the children of Syria with decimated limbs and lives, about all of it. If we believe that God is and God cares then it will make all the difference to the way that we live our lives and the way that we inhabit the world.

In all of our experiments in hope we are guided by the Jewish and Christian story, and by some parts of the story of Islam which brushes up against ours: the story of the one God who gives birth to all that is, and who in the Christ-child shows us what it truly means to be human, to be God’s imprint on creation, each of us uniquely reflecting God’s image in the world.

That story takes us through familiar scenes which have echoes in our own lives, some of which we’ve heard about in our readings tonight: the ravaging of the earth by flood waters and the promise that God will never choose to extinguish human life again; the visit of strangers to Sarah and Abraham, who in their old age offer generous, unquestioning, godly hospitality and in turn are trusted with bringing about a new generation; the repentance – the turning around – of the people of Ninevah; the gift of the Spirit, in us and in creation, whispering the truth of God’s presence, reminding us that all ground is holy ground; then Isaiah’s vision of a world where people are not driven from their own homes, but build houses and inhabit them, plant vineyards, eat their fruit, and live to a peaceful old age; and finally the hope, the promise, in Saint John’s revelation, that death itself will one day die.

How do we find the resilience needed to experiment with this hope – this hope of a God who is and a God who cares and a God who makes all things new – in the light of all that crushes it? How do we get up in the morning and listen to the news and remember that our mother has Alzheimers and our disabled neighbour has had her benefits withdrawn and that there are Muslim women being insulted by strangers who shout and spit and call them terrorists as they walk their children to school? How do we truly live with hope when that is our reality?

We do it intentionally and prayerfully and in a spirit of trust, informed by the Christian story and its fundamental claim that God never abandons us and is present in the tiniest interstices of the world. And so we are given the vision and the courage to see things differently.

Nick Baines, the bishop of Leeds, said recently: ‘Prayer is that exercise that, bringing us into the presence of God, gradually exposes us to the mind of God … Prayer invites us to be open and honest with God and one another – to tell the truth about our fears and anxieties as well as about the things that make us scream with joy. It’s like being stripped back so that we see as we are seen’. When we open our lives to God, to the possibility of God, and to the possibility of God caring deeply, that is prayer. And however we do it: quietly, loudly, angrily, questioningly, it changes us and the way that we see others.

After the Paris terrorist attacks a story did the rounds of social media, told by the American-Palestinian poet Naomi Shihab Nye. At an airport departure gate she discovers that her flight is delayed and shortly afterwards hears a second announcement: ‘If anyone understands any Arabic, please come to the gate immediately’. ‘Well,’ Naomi notes wryly, ‘one pauses these days’. But she did go to the gate and there she found an elderly Palestinian woman, distraught because she thought the flight had been cancelled and she needed to be in El Paso the next day for medical treatment.

Naomi spoke to her in halting Arabic, explaining that the flight was merely delayed and she would still arrive in time. This was enough to calm and befriend the woman, who, as that befriending spread amongst the people around them, who were of many different nationalities, began to offer Palestinian mamool biscuits among all the women at the gate. And Naomi tells us ‘To my amazement, not a single woman declined one. It was like a sacrament. And I looked around that gate of late and weary ones and thought, this is the world I want to live in. This can still happen anywhere. All is not lost’.

We experiment in hope by living prayerfully, seeing things in a new way, and trusting people: people who look and think and feel differently from ourselves and who reflect in the world something about God that we will never learn if we turn away from the stranger. Abraham and Sarah knew that. They welcomed three strangers in who changed their lives.

We experiment in hope prayerfully and trustfully and courageously. Courageously by refusing to freeze like rabbits in the headlights when the needs of the world or our neighbours or our family threaten to overwhelm us. The writer Mirabhai Starr says that this is what you should do when the crises and sorrows of the world overwhelm you and you don’t know where to begin: ‘You sit up and close your eyes and become quiet. Then you let your listening soften into being. From this space of stillness, tender compassion for the human predicament washes over you. One or two issues rise to the surface of your troubled mind (and) When you are finished with your meditation, you will pick one. You will stand up; you will speak out – you will not be afraid’.

We will stand up, speak out, will not be afraid because we have hope. The hope that God is and the hope that God cares and the hope that God is here: here in the span of the rainbow, in the strangers who touch our lives, in our repentance and turning around, in the Spirit implanted in our hearts, in a vision of social and political justice, in the promise of a new heaven and earth. Our hope is in the God who, again in the words of Malcolm Guite which we’ll hear later, ‘makes a womb of all this wounded world’ and comes among us as a child, a ‘tiny hope within our hopelessness’ ‘born, to bear us to our birth,/To touch a dying world with new-made hands’.

Let us experiment with hope sometimes wildly, sometimes tentatively, in joy, in heartbreak, with strangers, neighbours and friends. Let us do it prayerfully and intentionally, in honesty and openness with one another and with God, stripped back so that we see as God sees and are seen as God sees us. Allowing our fragility to break us open to the possibility of God in our midst, in one another, in ourselves, and in the coming of the Christ-child. And when we are called to act in that hope let us stand up, speak out and refuse to be afraid. And the one who was seated on the throne said, ‘See, I am making all things new’.